Because Earth is the only planet known to host life as we know it, researchers have usually focused on planetary systems similar to our own when searching for extraterrestrial life.

But new research suggests that planetary systems form differently around binary stars than they do around solo stars like the sun — and that those differences could affect the potential for a binary star system to support life. Nearly 50% all sun-size stars are binary stars, and if the team’s theory is confirmed, it could double the number of systems that researchers might want to probe.

“The result is exciting, since the search for extraterrestrial life will be equipped with several new, extremely powerful instruments within the coming years,” study lead author Jes Kristian Jørgensen, a professor of astrophysics and planetary science at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen, said in a statement. “This enhances the significance of understanding how planets are formed around different types of stars. Such results may pinpoint places which would be especially interesting to probe for the existence of life.”

Related: Why are we still searching for intelligent alien life?

The study was based on the observations of the young binary star system NGC 1333-IRAS2A using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) telescopes in Chile. That system, located about 1,000 light-years away, is enveloped in a disk of gas and dust that could one day create a planetary system. The team then created simulations that allowed them to rewind and fast-forward the life cycle of the system.

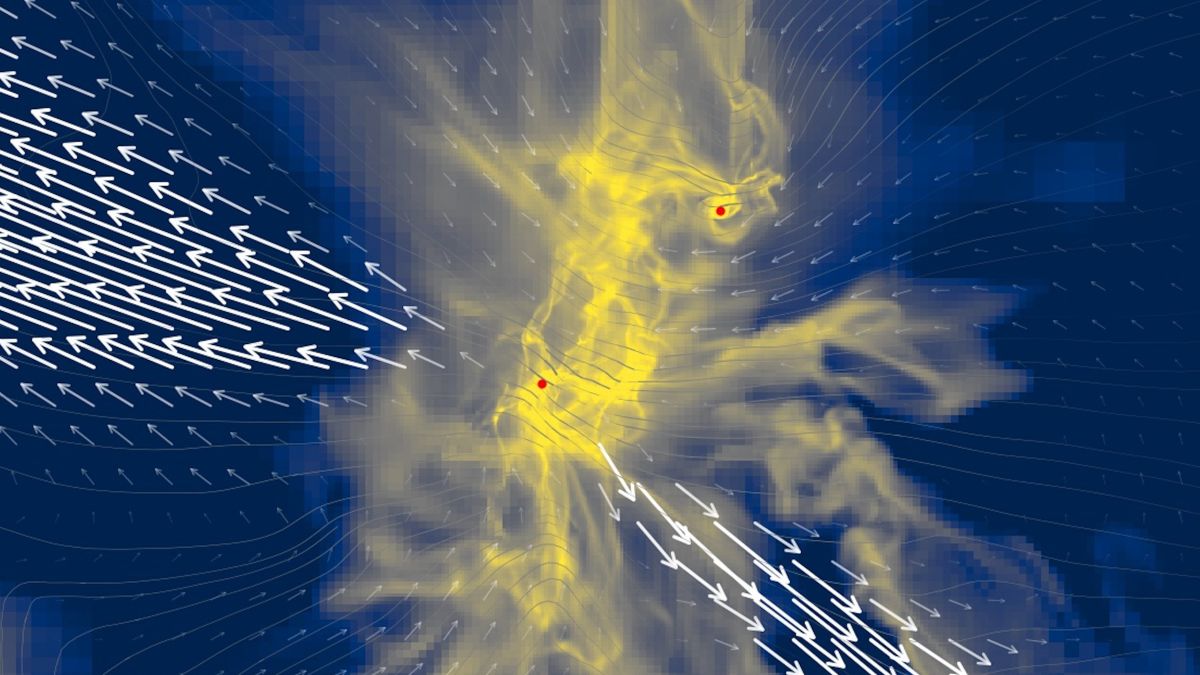

They discovered that the movement of the gas and dust was not continuous. “At some points in time — typically for relatively short periods of 10 to 100 years every thousand years — the movement becomes very strong,” the researchers said in a statement. “The binary star becomes 10 to 100 times brighter, until it returns to its regular state.”

The team theorized that at certain points in the stars’ orbits around each other, their gravity pulls material from the gas and dust disk onto the surfaces of the stars. In turn, these bursts of infalling trigger wobbly jets shooting out from the disk.

“The falling material will trigger a significant heating,” second author Rajika L. Kuruwita, a postdoctoral researcher at the Niels Bohr Institute, said in a statement. “These bursts will tear the gas and dust disk apart. While the disk will build up again, the bursts may still influence the structure of the later planetary system.”

Solo stars like the sun probably would not have gone through a similar process, which likely means that planets form differently around solo stars than they do around binary stars, the team said.

Researchers also plan to investigate the possible role of comets in planetary system formation, as comets carry organic molecules that could jump-start extraterrestrial life on an otherwise barren planet.

Related stories:

While the team hopes to continue their observations with ALMA, they’re looking forward to tapping into the next generation of telescopes, including the James Webb Space Telescope, Europe’s Extremely Large Telescope, and the Square Kilometre Array, all of which will begin operations within the next five years.

“Combining the different sources will provide a wealth of exciting results,” Jørgensen said.

The study was published May 23 in the journal Nature (opens in new tab).

Follow Stefanie Waldek on Twitter @StefanieWaldek. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.